Bladder stones in pets — dogs and cats mainly — are more than just uncomfortable; neglecting to treat them can be a death knell. Bladder stones, also known as uroliths, are rock-like accumulations of minerals that develop in the urinary bladder when they clump together and crystallize. These can irritate the bladder lining, be painful, cause infections, and in rare cases obstruct urine flow entirely — a veterinary emergency.

For many pets that have bladder stones that do not respond to diet or medical therapy, the initial attempt at surgical removal of a cystotomy is unsuccessful, and your surgeon may need to use the laser. In this blog post, we are going to dissect what you need to know about bladder stone surgery in pets and cover the bases of ‘what are stones, why does my pet need surgery, how surgery is performed, recovery details, prevention tips, and then cover off some real-life stats as well as expert commentary. So whether you’re a new or experienced pet owner, this guide will explain everything in simple words.

What Are Bladder Stones (Uroliths)?

Bladder stones are hard masses of minerals that form in the bladder when urine becomes concentrated and materials crystallize. These stones can be no larger than grains of sand or bigger, and they can fill the bladder. If they move into the urethra (the tube through which urine is drained), they can obstruct the flow, a life-threatening emergency if left untreated.

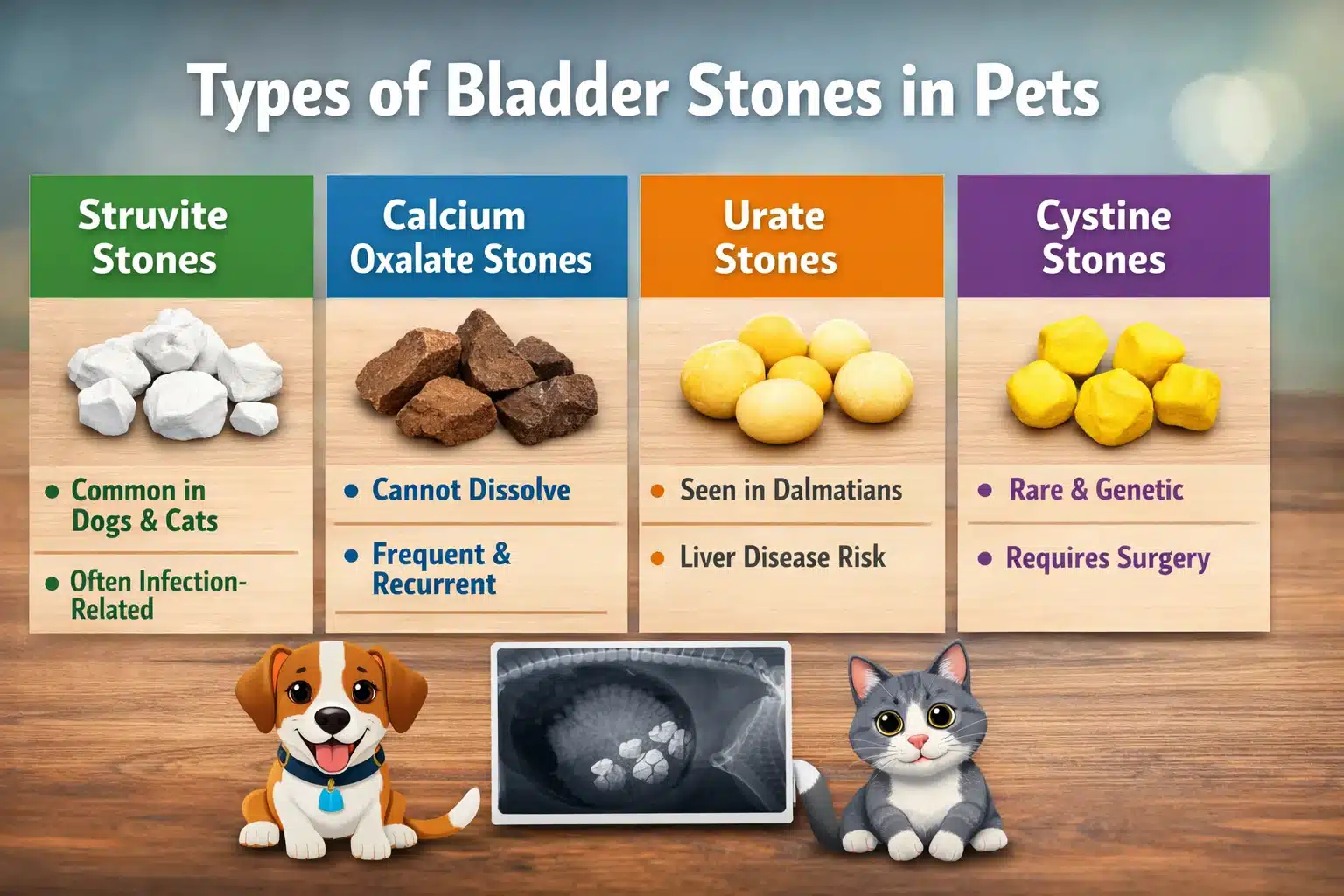

Types of Bladder Stones in Pets

Various types of stones are made from different minerals. Some of these are the following:

- Struvite Stones – More common in dogs and also found in cats.

- Calcium Oxalate Stones – These are most common in dogs and cats, and cannot be dissolved by diet.

- Urate Stones – Common in Dalmatians and animals with liver damage.

- Cystine Stones – Uncommon and are genetic in nature.

Each subtype affects the decision and risk of recurrence.

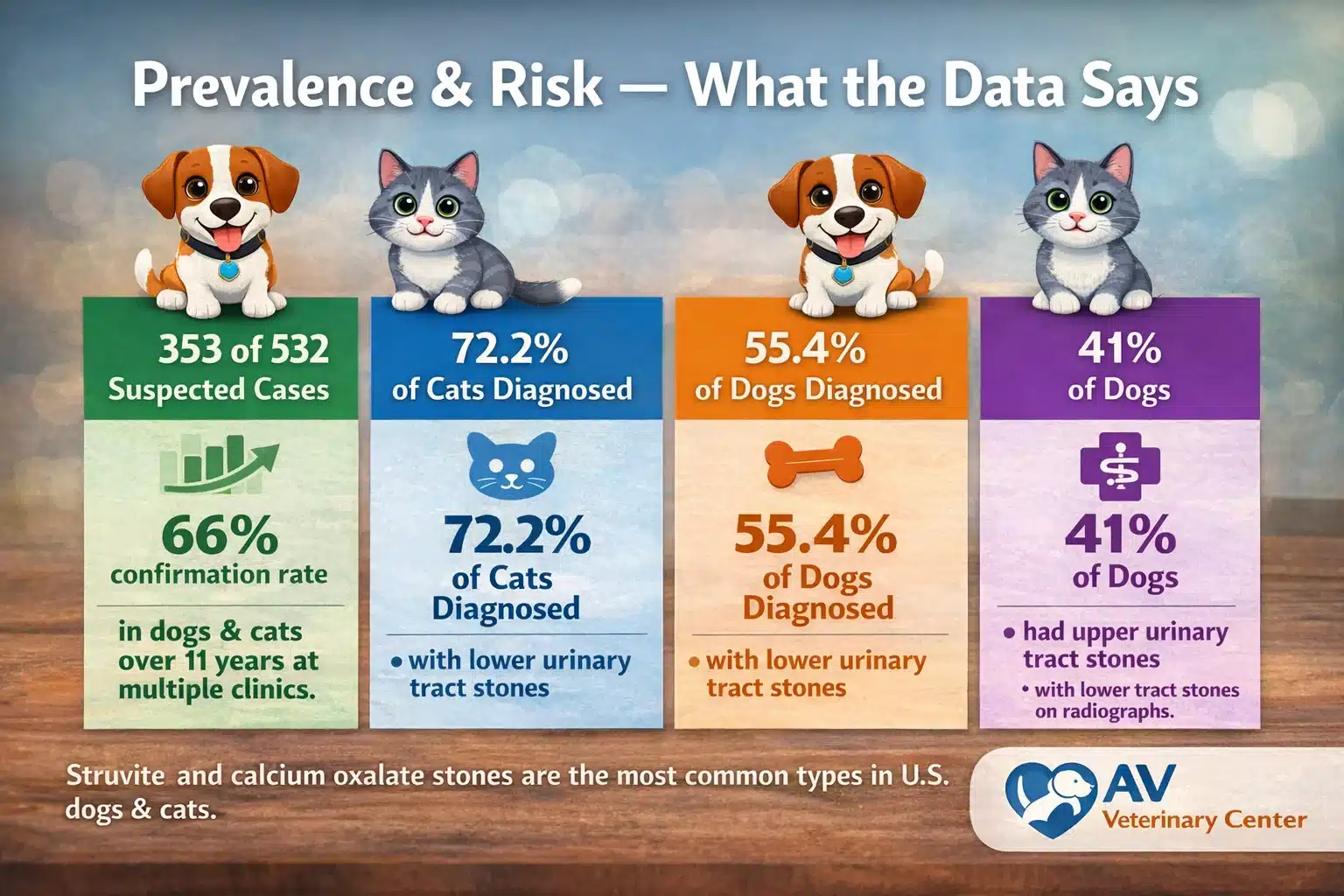

Prevalence & Risk — What the Data Says

Getting a sense of prevalence makes you realize just how common bladder stones really are:

| Statistic | Finding |

| Urolithiasis was diagnosed in 353 of the 532 cases suspected of having it | 66% confirmed in dogs & cats, more than 11 years of experience at several practices. |

| Proportion of cats with urinary stones in the lower urogenital tract | 72.2% in the study group |

| Percentage of dogs diagnosed | 55.4% in the same group |

| Dogs with lower urinary tract stones had upper tract stones as well | 41% showing radiographic findings |

| Stone types | Struvite & calcium oxalate stones are the most common |

These numbers reveal the fact that bladder stones are not an infrequently occurring problem in small animal practice, but rather a condition of great frequency.

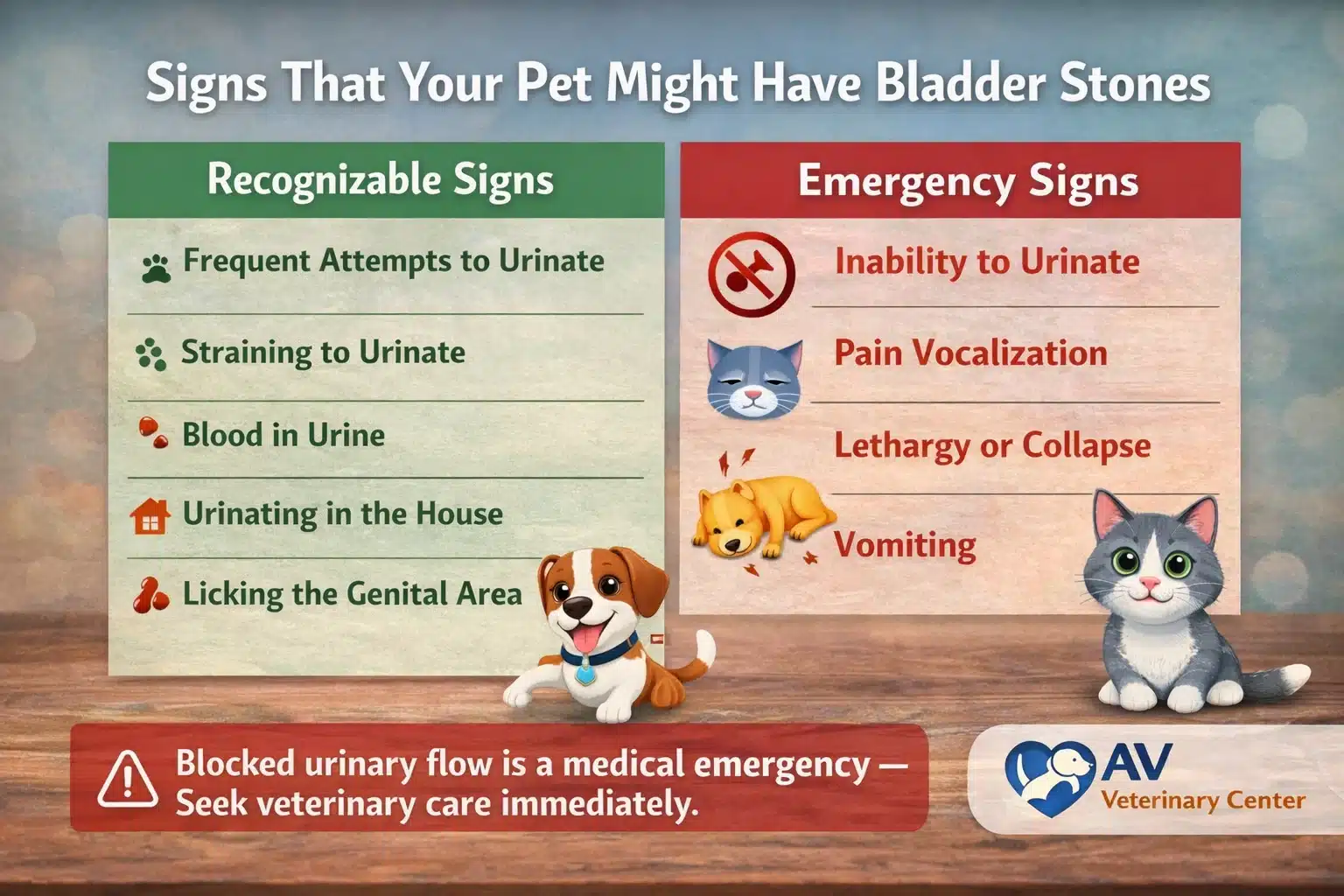

Signs That Your Pet Might Have Bladder Stones

Early Signs:

- Frequent attempts to urinate

- Straining with little or no urine

- Blood in the urine

- Licking the genital area

- Accidents in the house

Emergency Signs:

- Inability to pass urine (complete obstruction of the urinary bladder)

- Extreme pain or distress

- Vomiting or lethargy

If your pet cannot urinate at all, seek emergency veterinary care immediately.

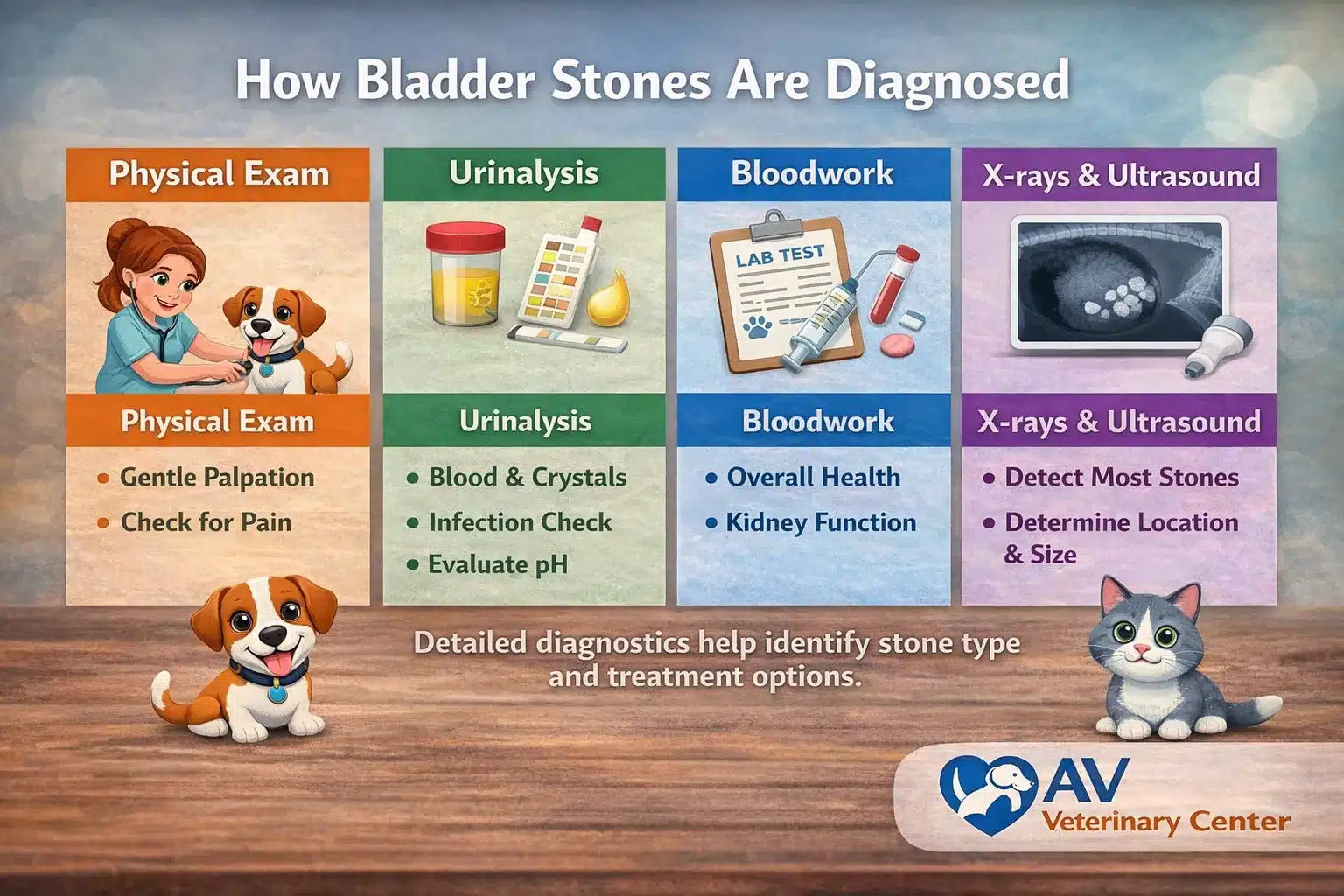

How Bladder Stones Are Diagnosed

Your vet will use a mixture of:

- Physical exam

- Urinalysis – screens for blood, crystals, infection

- Blood tests – measure the health of your organs

- X-rays and Ultrasound – to locate the stone, size, and quantity

The majority of bladder stones are radiodense and can be identified on X-Ray and ultrasound.

When Is Surgery (Cystotomy) Needed?

A cystotomy (surgical opening of the bladder) is indicated when:

Stones too big to pass by themselves

- If dissolution of the diet is unsuccessful, or if dissolution is not practically applicable

- There’s urinary obstruction

- Infections or bleeding return

- Pain is significant

Some struvite stones in dogs can be dissolved with dietary therapy over ~3 months, calcium oxalate stones will almost never dissolve and must be surgically removed.

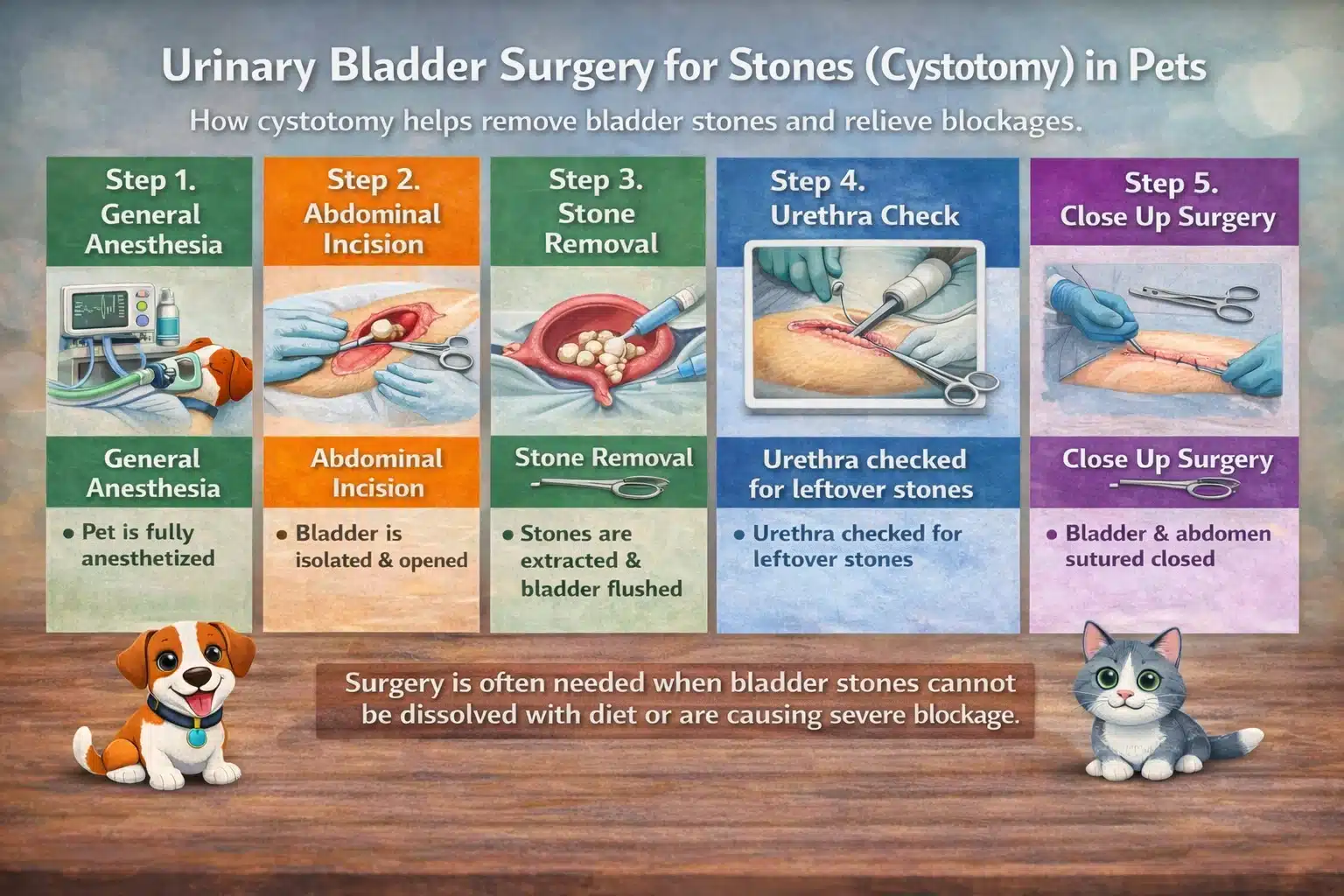

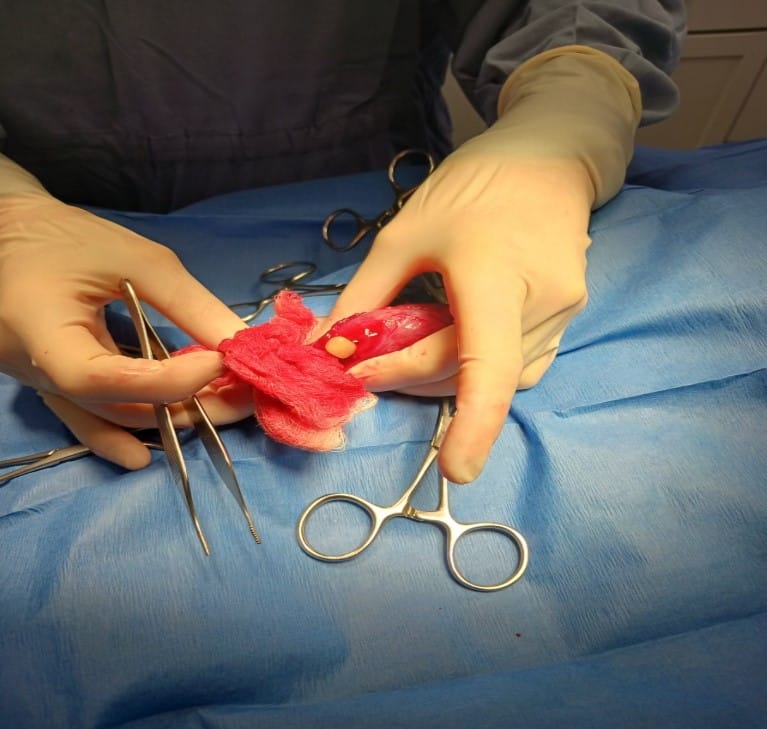

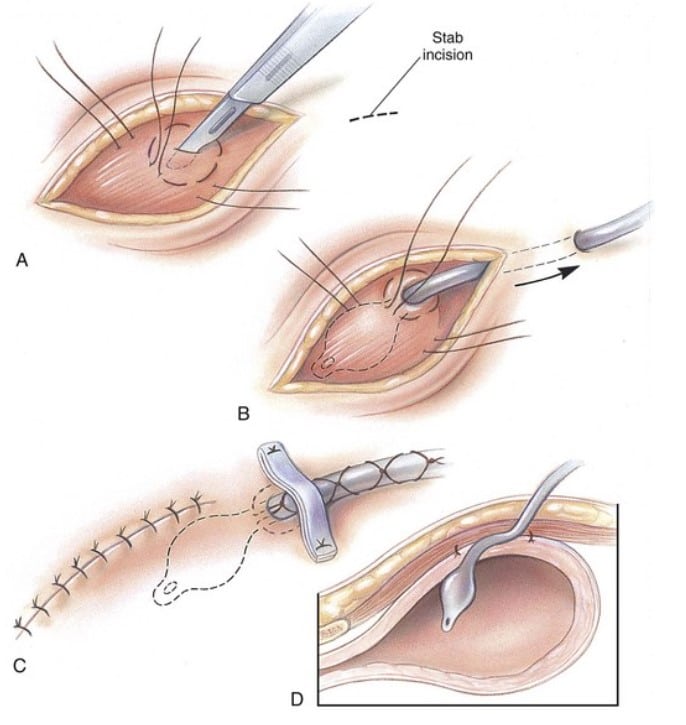

What Happens in Surgery (Cystotomy)?

Cystotomy involves:

- General anesthesia

- Abdominal incision

- The bladder is isolated and opened

- Stones are removed and flushed

- The bladder and abdomen are closed

During surgery, veterinarians examine the urethra and lining of the bladder for fragments of stone.

Comparison of Cystotomy Approaches

| Procedure | Description | Pros | Cons |

| Open Cystotomy | Traditional surgery | Direct stone removal | Longer recovery |

| Percutaneous Cystolithotomy | Minimally invasive technique | Faster recovery, fewer complications | Not suitable for all pets |

| Laparoscopic-Assisted Cystotomy | Uses scopes for guidance | Smaller incision | Specialized skills/equipment |

Each option has its time, and your vet will advise based on the size of the stone, the number of stones, and your pet’s health.

Recovery After Bladder Stone Surgery

Typical recovery plans include:

- Hospital stay: 1–3 days

- Activity restriction: 10–14 days

- Elizabethan collar (cone): Prevent licking

- Medication: Pain relief, antibiotics if infection is present

- Monitor urination and incision daily

With good care, most pets urinate and behave as usual.

“Recovery is going to be different from pet to pet, but early physical posture and urination within normal ranges are good signs.” — Veterinary Surgeon

Preventing Stone Recurrence

After surgery, stones can return if the root causes are not treated. Strategies include:

- Prescribed urinary diet for the prevention of stone formation

- Intake of more water (including the use of water fountains)

- Regular urine tests and imaging

- Treating urinary infections promptly

- In analyzing these stones after they are removed, for customized prevention

Quick Key Facts

- Bladder stones are also a common cause of lower urinary tract disease in pets, with struvite and calcium oxalate stones being the most common types seen in the United States. dvm

- Cystotomy is an old and established surgery, and many animals do well after the procedure. pubmed

- More recent, less invasive options, such as percutaneous cystolithotomy, may decrease hospital stay and recovery.

- Recurrence is not absent without prevention. royalcanin

Conclusion

Strip out your stone. A proven and effective way of alleviating pain, preventing life-threatening blockages, and getting your pet back to their normal selves is with bladder stone surgery – cystotomy. With accurate diagnosis and expert surgical care, as well as careful planning for prevention, many of these patients have a good outcome and return to a happy, active life following surgery.

If your pet has any urinary signs — especially straining, increased frequency of urination, or blood in the urine — don’t delay. Early veterinary intervention often means the difference between life and death.

Because in the end, when it comes to expert, compassionate care crafted for your four-legged family member, AV Veterinary Center can lead you through diagnosis, surgery, and recovery, with the right preventive measures in place.

FAQs

How do I know if my pet actually has bladder stones?

The majority of pet parents notice changes in urination first — straining, frequent trips outside, blood in the urine, or accidents in the house. Particularly in cats and male dogs, complete inability to urinate is a medical emergency. As they say, the only way to determine if bladder stones are present is through urinalysis and imaging (X-rays or ultrasound) performed by a vet.

Are bladder stones common in pets in the United States?

Oh yes, bladder stones are pretty common in U.S. vet practice, especially amongst dogs and cats with urinary tract disease. Studies from U.S. animal hospitals indicate that struvite and calcium oxalate stones are the most commonly diagnosed types. Some breeds, diets, and medical conditions can predispose.

Is bladder stone surgery safe for dogs and cats?

Yes. Cystotomy is a common and long-established surgery in U.S. veterinary practice. As with any surgical procedure, there are risks involved, but most pets recover both quickly and fully if the operation is done promptly and followed by appropriate aftercare.

How long does the surgery take, and will my pet stay overnight?

On average, the operation lasts 45 to 90 min according to the size and number of stones. Most stay in the hospital for 1 to 3 days so that veterinarians can monitor urination, pain levels, and healing prior to releasing them.